BLOG ARCHIVE

Roots of Bellefonte’s African Methodist Episcopal Church

Philip Ruth, Research Coordinator

April 30, 2024

At the urging of Thomas H. Fant, Presiding Elder of the AME Allegheny-Scranton District, I am drafting a history of Bellefonte’s St. Paul AME congregation and church building for use in an updated Pennsylvania Historic Resource Survey Form for the St. Paul AME Church building. We hope our submission of that Survey Form will result in the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission confirming the building’s eligibility for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. The following post is adapted from the first part of my draft history, which is chronologically organized and pitched to an audience of historians and historic preservationists. Readers will soon recognize that sorting out AME activities in and around Bellefonte before the Civil War is challenging, as two congregations were simultaneously active during that period: an AME Zion (a.k.a. “Wesleyan”) congregation, organized sometime prior to August 1834; and an AME (a.k.a.“Bethelite”) congregation, reportedly organized in 1844. The younger AME congregation is said to have absorbed members of the older AMEZ congregation in the mid-1840s.

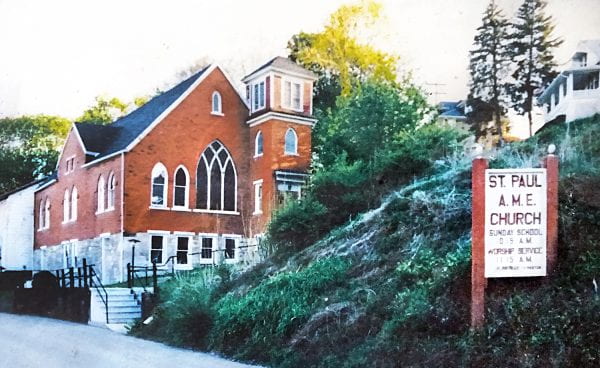

The brick church standing at 121 St. Paul Street in Bellefonte was constructed in 1910 by the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal (AME) congregation as an on-site replacement for the similarly-sized frame church the congregation had occupied for half a century. A fire believed to have been sparked by a furnace malfunction in the basement of the 50-year-old frame church in the early hours of Sunday, February 20, 1910, destroyed most of the structure, prompting the congregation to erect the present brick replacement within the next eight months.[i]

The roots of Bellefonte’s St. Paul AME congregation reach back decades before the brick church’s frame predecessor was built in 1859-1860 on the side of Halfmoon Hill in the borough’s West Ward. As early as August 1834, a 26-member African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ) congregation was active in Bellefonte, as noted in “Minutes of the Little York Conference” of the AMEZ Church recorded in that month.[ii] The AMEZ Church had been established by Black clergymen in New York City in 1821, in the wake of—and partly in response to—the founding five years earlier of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Philadelphia by the Rev. Richard Allen and others.[iii]

No records of either AMEZ or AME activities in or around Bellefonte prior to August 1834 have been discovered. The 26 persons reportedly comprising the borough’s AMEZ congregation in that month had likely been meeting for worship apart from Bellefonte’s white worshippers for at least a year or two. Before that, Black residents of the borough and adjoining sections of Spring Township wishing to participate in Christian services did so principally at Bellefonte’s Methodist Church, where the pastors and the great majority of congregants were white. Those pastors recorded 11 “colored” members in 1827, and 16 in 1828, along with approximately 380 white parishioners.[iv]

Members of Bellefonte’s nascent AMEZ congregation in 1834 were part of a notably large population of free-born and formerly enslaved Blacks drawn to the borough by employment opportunities in iron works, mills, hotels, restaurants, and private residences of well-to-do bankers, businessmen, jurists, and politicians. African Americans appear to have found in Bellefonte relatively congenial interracial relations (for that era), influenced by local abolition-supporting Quaker ironmasters and Methodist clergymen.[v] A federal census enumeration conducted in 1830 counted 131 Black men, women, and children living in Bellefonte and adjoining sections of Spring Township (including the residential area on the eastern slope of Halfmoon Hill, across Spring Creek from downtown Bellefonte[vi]). Over the course of the next decade, that number increased to 171, accounting for approximately 8% of the area’s total population in 1840, and 58% of Centre County’s Black population (which totaled 294[vii]).

In a historical sketch of Bellefonte’s “African Methodist” congregation published in 1877, longtime lay leader John Welch claimed that the borough’s AMEZ congregation was “organized in 1836 by Samuel Johnson, a minister and elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, in charge of the Chambersburg [Pennsylvania] Circuit of the Allegheny Conference.”[viii] Welch might have been a few years off in his assertion of an 1836 organization date, given the aforementioned report of Bellefonte’s AMEZ congregation already having 26 members in August 1834.[ix] Moreover, that congregation was established firmly enough by June 1836 to be included in a list of 13 “churches” represented at the Eighth Philadelphia Annual Conference of the AMEZ Church (the other churches were located in Philadelphia [2], Harrisburg, York, Carlisle, Shippensburg, Gettysburg, Chambersburg, Lewistown, Williamsport, Johnstown, and Pittsburgh [2][x]). It is also worth noting that the AMEZ Church’s Allegheny Conference was not established until 1849, so Samuel Johnson could not have been “in charge of the Chambersburg Circuit of the Allegheny Conference” in 1836, as Welch asserted.[xi]

Furthermore, Welch’s report that Bellefonte’s AMEZ congregation “was organized in 1836 by Samuel Johnson” is called into question by a recent contention that the congregation was founded instead by Maryland native David R. Stevens. An unsourced biographical sketch of Stevens published in One Hundred Voices: Harrisburg’s Historic African American Community, 1850-1920 asserts that, in addition to serving as an “incorporator, trustee, and deacon” of the Wesley A.M.E. Zion Church in Philadelphia,” Stevens “founded churches in Lewistown and Bellefonte, and a mission in Allegheny City (1839).”[xii] Indeed, Stevens was identified in the August 1834 Minutes of the Little York Conference as elder in charge of the Lewistown Circuit, comprising AMEZ churches in Lewistown (Mifflin County), Nippenose Township (Lycoming County), Northumberland (Northumberland County), and Bellefonte.[xiii]

No other nineteenth-century records linking the founding of Bellefonte’s AMEZ congregation to either David Stevens, Samuel Johnson, or any other clergyman have been found.

John Welch further asserted in 1877 that Bellefonte’s AMEZ congregation “was known as Zion’s Wesleyan A.M.E. church.” It “differed” from the later AME congregation (established in the borough in 1844) “only in form of government. The [AMEZ congregation] believed in electing superintendents every four years, while the [AME congregation] preferred ordaining bishops for life, or as long as their conduct comported with the Word of God.”[xiv] According to Welch’s successor as St. Paul AME historian—lay leader and veteran barber William H. Mills Sr., whose Brief History of the Origin and Organization of the A.M.E. Church of Bellefonte, Pa. was published in 1909—Bellefonte’s AMEZ adherents were sometimes referred to as “Weslayans,” while their AME counterparts were referred to as “Bethelites.”[xv] The latter name likely derived from the name of Philadelphia’s Mother Bethel AME Church, established in 1816 by the Rev. Richard Allen, founder and first bishop of the AME Church.[xvi]

In a Centre County deed dated March 29, 1838, Bellefonte’s AMEZ congregation was referred to as “a congregation of people worshiping in Bellefonte, members of the coloured Weslayan Methodist Episcopal Church of North America.” By that deed, Black Bellefonte barber John Coxe conveyed to three trustees of the AMEZ congregation a 600-square-foot lot fronting on E. Logan Street in the borough’s South Ward.[xvii] Within the next few months, the congregation erected on that lot a one-story house of worship “built of hewn logs, 26 feet front by 30 feet.”[xviii] The building would serve the congregation as both a meeting place and school house through the following decade.[xix]

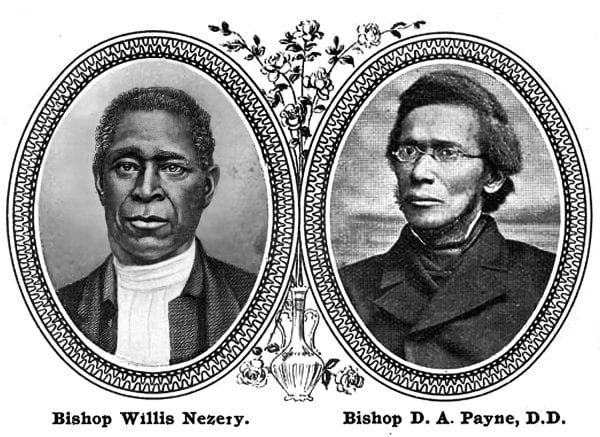

According to John Welch, the Rev. Willis Nazery organized Bellefonte’s alternative AME or “Bethelite” congregation in 1844.[xx] Nazery, whose surname was sometimes spelled “Nazrey,” had been born in Virginia in 1808. After his conversion in an AME church in New York in 1837, he was licensed to preach, and began serving as an itinerant preacher in 1840. The following year he was ordained as a deacon, and in 1843 was promoted to elder.[xxi] He may have been introduced to Centre County and Bellefonte in the early 1840s, after being transferred in 1841 from the New York Conference to the Baltimore Conference, and being “appointed to the Lewistown Circuit, in Pennsylvania.”[xxii] After organizing Bellefonte’s AME congregation “in 1844” (according to John Welch), Nazery moved to Morrisville, New Jersey, in 1845 “to lead Morris County’s first church organized by African Americans.”[xxiii]

Among Willis Nazery’s successors as itinerant pastor of Bellefonte’s fledgling AME congregation was future AME bishop James A. Shorter. A native of Washington, D.C., Shorter was admitted as a novice preacher to the Baltimore Conference of the AME Church in 1847, and was then “given the Lewiston Circuit charge, which consisted of Lewistown, Bellefonte, Mifflin, and Hollidaysburg.”[xxiv] As a “colleague of Rev. Isaac B. Parker,” pastor Shorter served the Lewistown Circuit for a year, before being ordained as a deacon in Baltimore’s Bethel AME Church and receiving an appointment to the Baltimore Conference’s Penningtonville Circuit (present Atglen, Chester County, Pennsylvania).[xxv]

John Welch seems a reliable informant concerning the founding and early years of Bellefonte’s “Bethelite” AME congregation, as he claimed in 1877 to be “the only one now living of the seven original members of the church.”[xxvi] Congregational historian William Mills Sr. later identified those charter members as day laborer Ephraim Caten and his wife Susan; their daughters Maria (married to day laborer Charles Green) and Margaret, with Margaret’s husband Samuel Powell; and day laborer John Welch and his wife Mariah[xxvii] (all of whom claimed on 1850 census schedules to have been born in Maryland). Mills further reported that “the first religious service by the A.M.E. society after the separation from the Weslayans was held at the residence of Ephraim Caten, who lived on West Lamb street [on Halfmoon Hill]. . . . The officiating minister on that occasion was Rev. Willis Nazery, whose services had been secured by Ephraim Caten, John Welch, and Samuel Powell. Rev. Nazery was a very exemplary minister, and served the people as their pastor for some time, gradually growing in popularity and distinction among African Methodists. He was later [in 1852] ordained Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal [Church], and is very commendably spoken of in Rev. Bishop Daniel A. Payne’s [1891] history of the church.”[xxviii]

From 1844 through 1847, Bellefonte’s AME congregation met in Ephraim and Susan Caten’s house on Halfmoon Hill, while its AMEZ counterparts gathered in their “hewn log” church-and-schoolhouse on E. Logan Street.[xxix] During that period, some of the AMEZ “Weslayans” switched their membership to the newer “Bethelite” congregation, leaving the AMEZ congregation in an “enfeebled condition,” according to William Mills.[xxx] As the AMEZ trustees had “little idea of financial matters, they ran heavily in debt and the [log] church was sold at Sheriff’s sale” in 1847, reported Centre County historian J. Thomas Mitchell in his 1941 biography of his great-grandfather, Quaker ironmaster William A. Thomas. Mitchell further reported that in 1847 the ironmaster, “with the aid of several of his ‘abolitionist friends,’ . . . erected on his own land, west of [Spring] creek and south of a continuation of High Street [on Halfmoon Hill], a ‘Meeting House and School House’ for [the use of the] negro population of Bellefonte, and also set aside a small tract of his land south of the new church and school to be used as a settlement for these people. On May 9, 1847 [Thomas] agreed to convey one lot of this tract to R.M. Parsons, a negro, in which he recites a former conveyance to another negro, Hudson Williams. This was the beginning of the negro colony [on Halfmoon Hill,] which still exists” in 1941.[xxxi] (The vacated AMEZ log church on E. Logan Street stood until it and several surrounding buildings were destroyed by fire in October 1879; its site is now a residential parking lot.[xxxii])

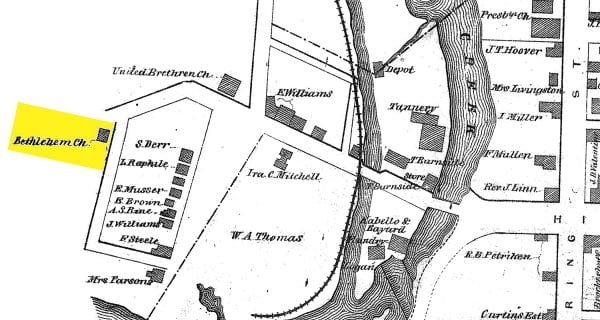

On a map of Bellefonte published in 1858, a rectangular structure denoted on or near the site of the present St. Paul AME church—along the north side of an unnamed alley on the alignment of present St. Paul Street—was labeled “Bethlehem Church.” Several residences depicted in a row along the alley immediately south of the church building were attributed to “W.A.T.,” referring to owner William A. Thomas.[xxxiii] The building labeled “Bethlehem Church” thus comports with Thomas Mitchell’s description of the frame “Meeting House and School House” erected on William Thomas’ land in 1847.[xxxiv]

The “Bethlehem Church” appellation, which has not been found in other historical accounts, might reflect the “Bethelite” affiliation of the only congregation still active in and around Bellefonte in 1858. That congregation had absorbed the remaining members of the “Weslayan” AMEZ congregation after the latter’s dissolution in 1847.[xxxv] In the process, the “Bethelites [had] increase[d] so rapidly in numbers, they were compelled to abandon the old home of father Caten as a place of worship and seek a more convenient place,” wrote William Mills. “After some considerable effort had been made by those noble fathers, they finally succeeded in securing a dwelling house from Mr. Frank Steele, a white gentleman, whose house was located on the alley leading up from South Thomas street [i.e., present Parson Alley, intersecting St. Paul Street 235 feet south of the St. Paul AME church]. This house they fitted up for a place of worship, and remained there for some time.”[xxxvi]

Though Mills further reported that “early in 1859 the [AME] officers moved to a one-story frame building which stood at that time adjacent to the present church edifice,” it seems more likely that the AME congregation moved into the “Meeting House and School House” on William Thomas’ land at least a decade earlier, following that building’s construction in 1847. Eyewitness John Welch reported more authoritatively that Bellefonte’s growing AME congregation met in private homes for several years following its organization in 1844, “then removed to a school house, where services were held until 1859.”[xxxvii] Welch’s chronology generally jibes with Thomas Mitchell’s report that “on March 27[, 1858,] William [A. Thomas] transferred to John Williams, John Welch and Ephraim Caton [sic] the ‘Meeting and School House’ building [on Halfmoon Hill], as trustees for the colored people of the town, subject to an annual payment of the sum of one dollar. These trustees and their successors continued to hold this property under that lease for over fifty years.”[xxxviii]

In the “small [frame] structure” on Halfmoon Hill that doubled “as a school house for colored children, many precious souls were soundly converted to God,” William Mills reported.[xxxix] John Welch attributed most of those conversions—which “increased the number [of local AME churchgoers] to thirty”—to the Rev. William Waugh Grimes.[xl] As reported in an 1877 biographical sketch:

[Grimes had been] born in Alexandria, Fairfax county, Va., September, 1824. He entered the [AME] church in 1843, was licensed to exhort in 1853, and licensed to preach in 1854. He joined the Baltimore Conference in 1855, and was appointed to Smyrna [Delaware] Circuit, being reappointed in 1856. During these two years he built [and/or rebuilt half-a-dozen AME churches in northern Delaware]. In 1857 he was appointed to the Eastern Circuit, and was put in jail for being in Maryland. From there he was transported out of the State as an abolitionist. In 1858 he was appointed to Frederica Circuit, Del[aware], and in 1859 to Lewistown, Pa.[xli]

From his pastoral base in Lewistown (seat of Mifflin County; 24 miles southeast of Bellefonte), William Grimes additionally served the Bellefonte and Altoona AME congregations in 1859 and 1860. During that productive term of service he “organized and built a church at Altoona,” while also spearheading an effort to replace the small AME church-and-schoolhouse on Halfmoon Hill overlooking Bellefonte with a “more commodious” and church-like structure.[xlii] By some accounts, pastor Grimes also functioned during that period as an agent on the branch of the Underground Railroad passing through Lewistown and Bellefonte en route to Punxsutawney, in Jefferson County, and a connection with the Railroad’s “Western Route in Pennsylvania.” In Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania (2008), William J. Switala alluded to Grimes in explaining “how the runaways got from Harrisburg to Bellefonte.” Citing information published by historian Charles L. Blockson in the 1980s and 90s, Switala wrote:

A number of towns between Harrisburg and Bellefonte had Underground Railroad stations. The most logical line of march between these two places was to leave Harrisburg and proceed for fifteen miles along the eastern bank of the Susquehanna, following the Paxtang Path, to the mouth of the Juniata River. From here, freedom seekers could travel up the Juniata, through Perry County, to the small town of Newport. Blockson indicates that there was a station here, as well as in several other towns in the general area. A review of his positioning of stations suggests two possible avenues for fugitives to follow . . . from Newport to Mifflintown. . . . Each of the towns on the route from Mifflintown onward had agents and stations to assist runaways. Mifflintown had a black agent named Samuel Imes, who would guide the fugitives to the next stop, Lewistown, on the Juniata River. Once there, he would entrust his charges to Rev. William Grimes, an itinerant black preacher and Underground Railroad agent. Grimes would take the fugitives along as he rode on his preaching circuit. The circuit ended at the town of Milroy, about seven miles [north of] Lewistown. In Milroy, Rev. James Nourse, pastor of the Milroy Presbyterian Church, took them into his home. Nourse had formed the Milroy Anti-Slavery Society and was an ardent abolitionist. Helping him in Milroy were Dr. Samuel Maclay, John Taylor, and Samuel Thompson. These agents guided the runaways from Milroy to Bellefonte, [16 miles northwestward] over the Seven Mountains. Two black conductors, Samuel Molston and Philip Roderis, also helped the cause in Milroy. The trail that they took from Milroy to Bellefonte most likely was the Kishacoquillas Indian Path. This old trail ran over the Seven Mountains and linked the two towns. From Bellefonte, the trail to freedom led to Punxsutawney and the Western Route of the Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania.[xliii]

Switala’s assertion that Lewistown-based pastor William Grimes’ “preaching circuit ended at the town of Milroy” is contradicted by multiple accounts (including those already cited) of Grimes serving congregations in Bellefonte and Altoona in 1859-60. If Grimes was truly inclined to “take the fugitives along as he rode on his preaching circuit,” he might have escorted freedom seekers to Bellefonte, or at least directed them to proceed there. Grimes was no doubt aware of persons living in and around the Centre County seat engaged in Underground Railroad activities, including abolition-supporting Quakers William and Eliza Thomas. As William Mills recalled in his 1909 history, William Thomas was “a wealthy white gentleman, a member of the Society of Friends, and also an unquestionable friend to the negro race. . . . [He was] also a bitter opponent to human slavery, like hundreds of other grand and noble men and women identified with the same Society of Friends. So strong was the sympathy of Mr. Thomas and his estimable companion, Mrs. Eliza Thomas, toward the fugitive slaves that their own fine private residence [at the northern foot of Halfmoon Hill; now 260 N. Thomas Street] often afforded a shelter and hiding place for many men, women and children fleeing from the cruel hand of slavery to a land of freedom.”[xliv]

Mills went on to identify several other “tried and true [white] friends, early residents of Bellefonte in the dark days of servitude, for the reason that they were men of high character, noble principles and aversion to human slavery, each of them being directly or indirectly connected with what was known in those days as the ‘under-ground railroad.’” They were “George Valentine, Sr., founder of the Valentine iron works; Bond Valentine, Sr.; Abraham Valentine, Sr.; Robert Miller, Sr.; and Ex-Governor [Andrew Gregg] Curtin, dec’d., all heads of the first families of Bellefonte.” In Mills’ view, “the specific labors of those true and sympathetic men and their very estimable wives can never be estimated by our yet struggling race for the interest which they manifested in rescuing and piloting men, women and children to a place of refuge, Canada being the principal house of refuge. No time nor means were spared by those eminent friends in shipping the fugitives to a land of freedom and safety, from the clutches of the master, cruel slave driver and the kidnapper.”[xlv]

In pastor William Grimes’ effort to build a “more commodious” AME church in Bellefonte in 1859, he was assisted by trustees Ephraim Caten, John Williams, and George Sims Sr. As William Mills reported in 1909:

These men, actuated by the purest motive, formed themselves into a committee and consequently resolved to call upon Mr. William A. Thomas . . . to solicit his aid in securing a more convenient place in which to worship. Out of the goodness of this gentleman’s heart, and the unfeigned sympathy of both him and his estimable wife for this struggling church, they resolved at once that the petition of the committee should be granted. In consequence, Mr. Thomas deeded to the A.M.E. society the lot upon which the present [circa-1860 frame] church edifice has been erected, and which is to be retained by the A.M.E. church as long as religious services are conducted by them in this edifice. The deed has been legally signed by Mr. William A. Thomas and his wife Eliza Thomas, and remains [in 1909] in the possession of the trustees of the A. M. E. church in Bellefonte, Pa.[xlvi]

The deed cited by Mills has not been located, nor is there any reference in Centre County’s Grantor-Grantee Index to a conveyance of real estate by William A. Thomas to representatives of the AME congregation during Thomas’ lifetime. Perhaps the deed was never presented to Centre County’s Recorder of Deeds for recording. Was it burned in the February 1910 fire that destroyed the St. Paul AME frame church? In any case, two weeks after that fire, a trustee under the will of the late William A. Thomas conveyed the church property to trustees of Bellefonte’s AME congregation by a deed later duly recorded. In that instrument, the 4,875-square-foot parcel on which the AME frame church had stood for 50 years was described as follows:

Bounded on the North by a proposed extension of High Street, known as the road up Half-Moon hill, on the east by St. Paul Street; on the south by other land of [William A. Thomas’] Estate, now occupied by Maria Green; and on the west by a road leading up said Half-Moon hill; having 65 feet frontage on its northern and southern sides and 75 feet frontage on its eastern and western sides; and being the same premises which William A. Thomas, in his lifetime, did set apart for the use of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.[xlvii]

According to that description, the lot occupied by the frame AME church on Halfmoon Hill from 1860 through its burning in February 1910 contained 4,875 square feet or 0.11 acres. The parcel’s relatively small size, steeply sloped surface, and stony composition rendered it unsuitable for burials. As discussed below, Bellefonte’s AME congregation doesn’t appear to have ever had a dedicated burial ground. Between 1806 and 1856, deceased members of the congregation may have been buried alongside the remains of white citizens in the borough’s public “Grave Yard” on the hill east of the courthouse. Following the Union Cemetery Association’s incorporation of that burial ground into a much larger “Union” cemetery in 1856, scores or perhaps even hundreds of Black Bellefusians were buried in a section of the expanded burial ground along Howard Street—most of them in unmarked graves.[xlviii]

Construction of the limestone foundation walls of the new AME church on Halfmoon Hill began in 1859, as recorded on a datestone incorporated into the foundation of the present brick church.[xlix] The frame superstructure of the AME church was completed in the spring or early summer of the following year. Pastor Grimes and the building committee scheduled a dedication service for late July 1860, inviting AME bishop Daniel A. Payne to deliver the dedicatory sermon. By the time of his ordination as the AME Church’s sixth bishop in 1853, Payne had also served as a “leader in the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, which provided food, clothing, and temporary shelter for fugitives from slavery. He also assisted them in escaping to Canada which did not recognize the Fugitive Slave Act” of 1850.[l]

At the dedication service held in the new church on Sunday, July 29, 1860, Bishop Payne was joined by pastor Grimes, the Revs. James D. Lynch and Alexander W. Wayman of the Baltimore Conference, Christian Recorder editor Benjamin T. Tanner, and “a large concourse of people both white and colored,” as William Mills later recalled[li] (the Rev. Tucker’s participation was recollected only by John Welch[lii]). “It was a grand day for the society of African Methodists in Bellefonte when they were no longer compelled to suffer the inconvenience of worshiping from house to house,” Mills continued.[liii] His reportage is supported by an article published a few days after the dedication in Bellefonte’s virulently anti-abolitionist Democratic Watchman. The article’s writer observed that “a large number of our white population attended the services. The preaching is represented as of a high order [and] the state of church finances is said to be in a promising condition.”[liv] Bishop Payne lingered in Bellefonte long enough to deliver a sermon in Bellefonte’s Methodist Church, at the invitation of pastor Thomas Sherlock. A report in the Democratic Watchman opined that Payne was “an excellent preacher.”[lv]

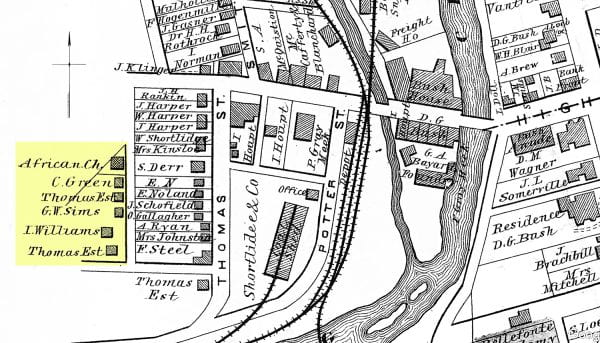

A drawing of the AME congregation’s new home on Halfmoon Hill, published in the Democratic Watchman, depicted an open-gable-roofed frame building approximately 24 feet tall, 24 feet wide, and 48 feet long, standing on stone foundation walls rising approximately eight feet from the ground on the façade fronting on St. Paul Street.[lvi] On a map of Bellefonte and Spring Township published in 1861, the structure’s rectangular footprint was depicted as roughly twice the size of the footprint of the preceding “Bethlehem Church,” denoted in that location on the 1858 map.[lvii] The 1861 cartographer labeled the new AME building “Bethlehem Ch[urch].” On a map of Bellefonte published in 1874—eight years after Bellefonte annexed from Spring Township the eastern half of Halfmoon Hill—the AME church was labeled “African Ch[urch].”[lviii]

Charles Blockson came to believe that the building dedicated in July 1860 was used to hide and accommodate freedom seekers until January 1863, when President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. In his 1981 book The Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania, Blockson noted that “Centre County has a rich heritage of social activism, and blacks playing a leading role in that history. Due to the strong anti-slavery influence in Bellefonte among a small group of Quakers, many of the fugitive slaves from the southeastern states, after reaching Centre County, settled in Bellefonte and other small towns. The county’s largest black population was located here. St. Paul’s A.M.E. Church, organized in 1859 [sic], is reputed to have served as a station on the Underground Railroad.”[lix] During visits to Bellefonte in the 1990s and early 2000s, Blockson expressed a firm belief that the frame AME church on Halfmoon Hill had been used as a hiding place for freedom seekers. In June 2002, for instance, his address to an audience assembled in the St. Paul AME church included assertions that the “church that was once a stop on the underground railroad” and “must be preserved” (according to a newspaper report). He later elaborated that “some self-liberators . . . seek[ing] freedom in Canada and free states . . . stayed at the Bellefonte church before moving on to the Williamsport and Lycoming County areas.”[lx] How Blockson came to believe that the frame AME church on Halfmoon Hill harbored “self-liberators” is not explained. Unaccountably, none of the five AME churches identified by Blockson in his 1994 Hippocrene Guide to the Underground Railroad as “Pennsylvania Sites Traditionally Associated With The Underground Railroad” were located in Centre County.[lxi] It should also be noted that William Mills, in discussing “under-ground railroad” activities in Centre County in his 1909 history of the St. Paul AME congregation, did not characterize the AME church on Halfmoon Hill as a shelter or station. Nor have any nineteenth-century first-person accounts or third-person reports been found to support that notion.

According to William Mills, “at the expiration of Rev. Grimes’ term as pastor [of Bellefonte’s AME congregation in 1861] there followed a succession of ministry, the church gradually progressing until at present [1909] it has a membership of fifty-five.”[lxii] That early “succession of ministry” involved pastors with either AME or AMEZ credentials serving Bellefonte’s AME congregation as part of multi-congregation circuits, in which case they might hold services in the borough only a few times each year. For instance, in 1865 AME pastor John H. Spriggs held “quarterly meetings” and “love feasts” in Bellefonte as part of his Hollidaysburg Circuit charge, which also included congregations in Altoona and Williamsport.[lxiii] Of the quarterly meeting Spriggs conducted in Bellefonte on Sunday, December 3, 1865, he reported:

We had a splendid meeting all Sunday. The members say that it was the best one they have had for two years or more. The members of Bellefonte do not fancy to have a white man to administer the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. I cannot tell the reason why they have this objection. On that account they have not had the sacrament administered to them for three quarterly meetings. We have had love feasts regularly with them. The Bellefonte church is very much in debt, and they say that they cannot pay for their church while they have to take all they can raise to support the preacher, and then cannot raise the quota for that church. But they hope that Conference will send a preacher without a family, next year, on the circuit. The membership is very small in Bellefonte. They have a good Sabbath school; and the best church [building] in the entire circuit is at Bellefonte, and if there is not some arrangement made to pay for it, we will lose what we have gained.[lxiv]

Through the latter 1860s and early 1870s, Bellefonte’s AME congregation continued to be served by itinerant pastors in charge of central Pennsylvania circuits, including the Revs. J.S. Wilson and Walter Scott Lowry.[lxv] The latter was appointed by the AME Pittsburgh Conference to “the Bellefonte Circuit” in November 1869 (as noted in an obituary). Pastor Lowry “first met the annual conference in Pittsburg[h during the summer of] 1870, reporting the best year’s work that Bellefonte had ever made; over seventy conversions in about six months. Bishop Brown, acting for Bishop Payne, [reappointed] Brother Lowry to Bellefonte. [Lowry] had some unpleasant experiences on his way back to his work. At Tyrone [a railroad town 28 miles southwest of Bellefonte] he was obliged to lie over all night. Prejudice would not allow to him the common treatment given to travelers; so he was obliged to camp in the mountains all night. In the fall of 1870 he entered Wilberforce University.”[lxvi]

Bellefonte’s AME congregation established a more formal and regular Sunday school program in the mid-1860s, with John Welch serving as superintendent. Visiting overseer Rev. Elisha Weaver filed the following report of the program’s early success in August 1867:

At a Sunday-school held in the borough of Bellefonte, I was much pleased and gratified to see the number of scholars in attendance, and also at their respectable appearance, and the general good order. The school is evidently in its infancy as yet, but is, I believe, making good progress, and under the benevolent and judicious superintendence of Mr. W[elch], it will doubtless prosper and prove an advantage to many, by affording the means of obtaining knowledge of a religious nature which could not otherwise have been obtained. Many of the scholars can read well, but the majority of them are only becoming familiar with their letters. The teachers, who are principally females, manifest an earnest devotion to the work of instructing the young. The only obstacle in the way of a rapid advancement of the school seems to be a want of proper books. It is to be hoped that this deficiency may be immediately supplied.[lxvii]

Another perspective on the AME congregation’s activities and challenges at this time—offered by the editor of Bellefonte’s Democratic Watchman—was presented in that newspaper’s “Bellefonte’s Churches” review of January 18, 1867, as follows:

The “African Methodist” Church [stands] at the foot of the hill on Cheapside [a nickname for the Borough’s West Ward, on the west side of Spring Creek]. It has no regular preacher and has a very irregular attendance, except on the part of about a half-dozen members, whose example of Christian devotion, might be followed, by many of the members of other churches, to considerable benefit. The church edifice is small, but sufficiently large to accommodate all who attend at it. There are plenty of negroes in Bellefonte [144 enumerated in the 1850 Federal census] to make up a good sized congregation, but they are not troubled with religious zeal. . . . There are a few members of this church who keep it up, and whose actions lead one to believe that they are truly zealous. The building is in comparatively good condition, but has neither choir nor instrument.[lxviii]

According to the Rev. Amos A. Williams, at the Pittsburgh Annual Conference of the AME Church “held at Meadville Pa. [circa spring 1872], Bellefonte was made a Station”—meaning the Conference committed to supporting a full-time pastor in the borough.[lxix] The first pastor appointed to the new station was Williams himself, who was then “stationed at Bellefonte for two years and eight months” (April 1872 through December 1874).[lxx] Upon his arrival in the Centre County seat, pastor Williams found only a “few [AME] members here, but they are doing a noble work.” As with all AME congregations, it was the pastor’s responsibility to raise money for his own support and to help fund Conference oversight. Williams noted in April 1873 that he had collected

a dollar from every member [of the congregation], and they are pleased with the “One Dollar” system.’ Our Sunday school is in fine working order. We use the International Uniform lesson [booklet]. Our 13th Jubilee (or anniversary) was held some time since. The pupils enjoyed it finely. Revs. J.W. Steward, of Williamsport, and G.H. Steward, of Altoona, were with us and made very interesting remarks. Mr. S.S. Lyons has presented a fine Mason & Hamlon Cabinet Organ to our school. He has also given $250 towards ministers’ support. He promised to continue this gift yearly if the people of color will improve themselves in morality, industry, spiritual and intellectual education.[lxxi]

“S.S. Lyons” was white Bellefonte bookkeeper Samuel Stewart Lyon, married to Anna Valentine, a daughter of Quaker ironmaster Abraham S. Valentine and his wife Clarissa (née Miles).[lxxii]

The earliest references to the AME church on Halfmoon Hill as “St. Paul’s Chapel” appeared in print during Amos Williams’ pastorate in Bellefonte. The Rev. W.S. Lowry referred to the church by that name in his November 27, 1873, report in the Christian Recorder of a meeting of “several quarterly conferences, composing the Altoona District of the Pittsburg Conference,” over which Pastor Williams served as Presiding Elder. The five-day meeting was held in “St. Paul’s Chapel, Bellefonte, Pa.,” in early October 1873. During the session in which “the needs of the District” were discussed, the AME building on Halfmoon Hill was characterized as “a fine commodious church.” Bishop Payne was applauded for having “sent a good workman here in the person of Elder Williams, who is instrumental in doing great work here.”[lxxiii]

In an 1874-75 directory of Bellefonte, Amos Williams was identified as the pastor of “St. Paul’s African M. E. Church,” reported to have 36 members. Its Sunday school, now under the supervision of Samuel S. Lyon, served 84 “scholars.” The congregation’s trustees were identified in the directory as John Welch, barber Meshic S. Graham, sexton Walter Rose, and Prof. J.C. Hawkins of Allegheny City, who also served as librarian.[lxxiv]

At the May 1875 Annual Session of the Pittsburgh AME Conference, John Coleman, “of Ohio Conference,” was appointed to the pastorate at “Bellefonte Station.”[lxxv] Former Bellefonte pastor (now bishop) A.W. Wayman described “Brother Coleman” in December 1876 as “one of the sons of Wilberforce [University],” and reported Coleman’s reputation as “a young man of great promise.” Wayman finally met pastor Coleman when the bishop visited Bellefonte in the fall of that year, during a swing through northern and central Pennsylvania. Of that meeting, Wayman wrote the following in the Christian Recorder:

On Wednesday [November 1, 1876] I left Wilksbarre [sic] for Bellefonte. Rev. John Coleman is the minister in charge of this good old circuit. It was once connected with the Baltimore Conference, for many years. The late Bishop Nazrey spent his first itinerant days there, as did also the present Bishop [James A.] Shorter. Before the passage of the Fugitive Slave Bill [in 1850], there was a great many of our people in that part of the country; they scattered then to Canada, and other parts. The [AME] Zion Church was then the leading denomination all through that part of the State; but I am told that they have nearly all disappeared. . . . I had not visited this place since [the church dedication in July] 1860. A great many of the old heads are gone, and there is almost a new congregation.[lxxvi]

Those remarks by Bishop A.W. Wayman conclude these notes on the “Roots of Bellefonte’s African Methodist Episcopal Church.” Activities and key developments in the life of the “almost new [St. Paul AME] congregation” after Wayman’s 1876 visit will be addressed in subsequent posts.

[i] Democratic Watchman 1910a:8; 1910b:4; 1910c:4

[ii] Moore 1884:389-90

[iii] Moore 1884:12; Allen and Tapisco 1817:10

[iv] Linn 1883:262

[v] Melander 1981:223-229; Linn 1883:262

[vi] United States Bureau of the Census 1830

[vii] United States Bureau of the Census 1840

[viii] Welch 1877:308

[ix] Moore 1884:124

[x] Moore 1884:124

[xi] Moore 1884:134

[xii] Jackson et al. 2020:125

[xiii] Moore 1884:124

[xiv] Welch 1877:308

[xv] Mills 1909:2

[xvi] Howell 2023:n.p.

[xvii] Centre County Deed Book 13:232

[xviii] Ruth 2022:n.p.

[xix] Mitchell 1941:86-87

[xx] Welch 1877:308-09

[xxi] Wright 1915:280

[xxii] Handy 1902:193

[xxiii] Coughlin 2012:n.p.

[xxiv] Wayman 1876:n.p.

[xxv] Wayman 1890:19

[xxvi] Welch 1877:309

[xxvii] Mills 1909:2; United States Bureau of the Census 1850

[xxviii] Mills 1909:2-3; Payne 1891:127

[xxix] Welch 1877:308

[xxx] Mills 1909:3

[xxxi] Mitchell 1941:87

[xxxii] Ruth 2022:n.p.

[xxxiii] Hopkins 1858

[xxxiv] Mitchell 1941:87

[xxxv] Welch 1877:309

[xxxvi] Mills 1910:3

[xxxvii] Welch 1877:308

[xxxviii] Mitchell 1941:107

[xxxix] Mills 1909:3

[xl] Welch 1877:308

[xli] Morgan 1887:30-31

[xlii] Morgan 1887:31; Mills 1909:3

[xliii] Switala 2008:113-114

[xliv] Mills 1909:3-4

[xlv] Mills 1909:5

[xlvi] Mills 1909:3-4

[xlvii] Centre County Deed Book 108:205

[xlviii] Linn 1883:98; Publications Committee of the Centre County Genealogical Society 2010:188

[xlix] Democratic Watchman 1910b:4; Mills 1909:6, 9

[l] Wada 2008:n.p.

[li] Mills 1909:6

[lii] Welch 1877:308

[liii] Mills 1909:6

[liv] Democratic Watchman 1860:3

[lv] Democratic Watchman 1860:3

[lvi] Democratic Watchman 1895:6

[lvii] Walling 1861; Hopkins 1858

[lviii] Nichols 1874

[lix] Blockson 1981:105-106

[lx] Smeltz 2002:A2

[lxi] Blockson 1994

[lxii] Mills 1909:7

[lxiii] Spriggs 1865a:n.p.; 1865b:n.p.

[lxiv] Spriggs 1865b:n.p.

[lxv] Weaver 1866:n.p., 1887:n.p.

[lxvi] Weaver 1887:n.p.

[lxvii] Weaver 1867:n.p.

[lxviii] Democratic Watchman 1867:3; United States Bureau of the Census 1870

[lxix] Williams 1873:n.p.

[lxx] Williams 1875:n.p.

[lxxi] Williams 1873:n.p.

[lxxii] United States Bureau of the Census 1870; Greevy and Renner 1874:161; Klitz 2013:n.p.; Mills 1909:15

[lxxiii] Lowry 1873:n.p.

[lxxiv] Greevy and Renner 1874:161, 195

[lxxv] Thomas 1875:n.p.

[lxxvi] Wayman 1876:n.p.

I look forward to your research which will help me answer my own questions about Blacks living in Bellefonte.

I read a great article about the Mills bros from Bellfeonte. I grew up in State College and left to go West as a registered nurse. I ran into a social worker and told her that I was born in Bellefonte and surprisingly she said her aunt married a man from Bellefonte who ironically was a Mills Bros. relative. This lead me to do research and I found out about the Underground Railroad. As a native I never knew about this part of the railroad. See the attached article: The Mills Brothers Trace Roots to Bellefonte

Thank you for posting this biography of Adeline. My grandmother knew her. She lived with us when I was growing up and told me a lot of stories about her childhood in Bellefonte. I was actually thinking about Adeline and wondering if there was ever a way to know any information. AG Curtin was my granny’s grandfather and she lived in his house when she was a child, she was born in 1890 and lived in Bellefonte because her mother, Curtin’s youngest daughter, had an illness and so my grandmother spent most of her time with Adeline in the kitchen or on outings and she spoke very fondly of what a great person Adeline was and wonderful memories she had. It was interesting to read this because I had forgotten some of her stories. I think the minister or pastor of that A.M.E church used to also work for Gov. Curtin as his horse and buggy driver when he was governor and also owned the barber shop, was friends with Frederick Douglas who got his haircut there)and his grandchildren were the singing group called The Mills Brothers.

Anne: Any chance your family has photographs taken in an around Bellefonte during the 1800s or early 1900s?

Anonymous received by email:

“Consider me an ardent admirer/encourager of your group’s work, and please let me know how I might best become aware of your discoveries.

The item that particularly struck me from the recent article was the existence of the Scotia/Marysville black communities, and the information that Quaker Isaac Way’s 1850 household records included 13 black children. That boggled my mind! I knew of the significant role of the Quaker Valentines and Thomas in Bellefonte regarding the black community there, but I had never heard that fact about a Halfmoon Quaker family.“

Hello. Can you post the link about Scotia/Marysville Black communities you referenced here. I would enjoy the read as well! Or, send: rdn11@psu.edu. Thank you.

What a lovely blog!

I too have a long maternal ancestral line in Bellefonte and Pennsylvania: Harding/Van Zandt/Rice/Green/Jackson/Delige/Pennington. Some of my Hardings (my g-grandmother Viola, her aunt Margaret (Mag/Maggie), cousins William and Harry all migrated to Harrisburg where I am from, so I know they would have known your Thompson relative. I unfortunately don’t know a lot about their lives in Bellefonte, other than what I’ve found in my genealogy research. My My g-grandmother Viola died when I was 3 years old in 1963, and my last great-aunt (her daughter also named Viola) passed away at 97 in 2010, but for some reason, she wouldn’t share when I asked her specific questions about her family. Interestingly enough, after she passed, I found a couple of narratives she did in her county and few years before that I didn’t know about until then.

Anyway, very nice work! It gives me hope that I might someday gather enough solid information to share.